Venezuela: Why Maduro’s Arrest Cannot Be The Last Act

David Ortiz, University of Chicago

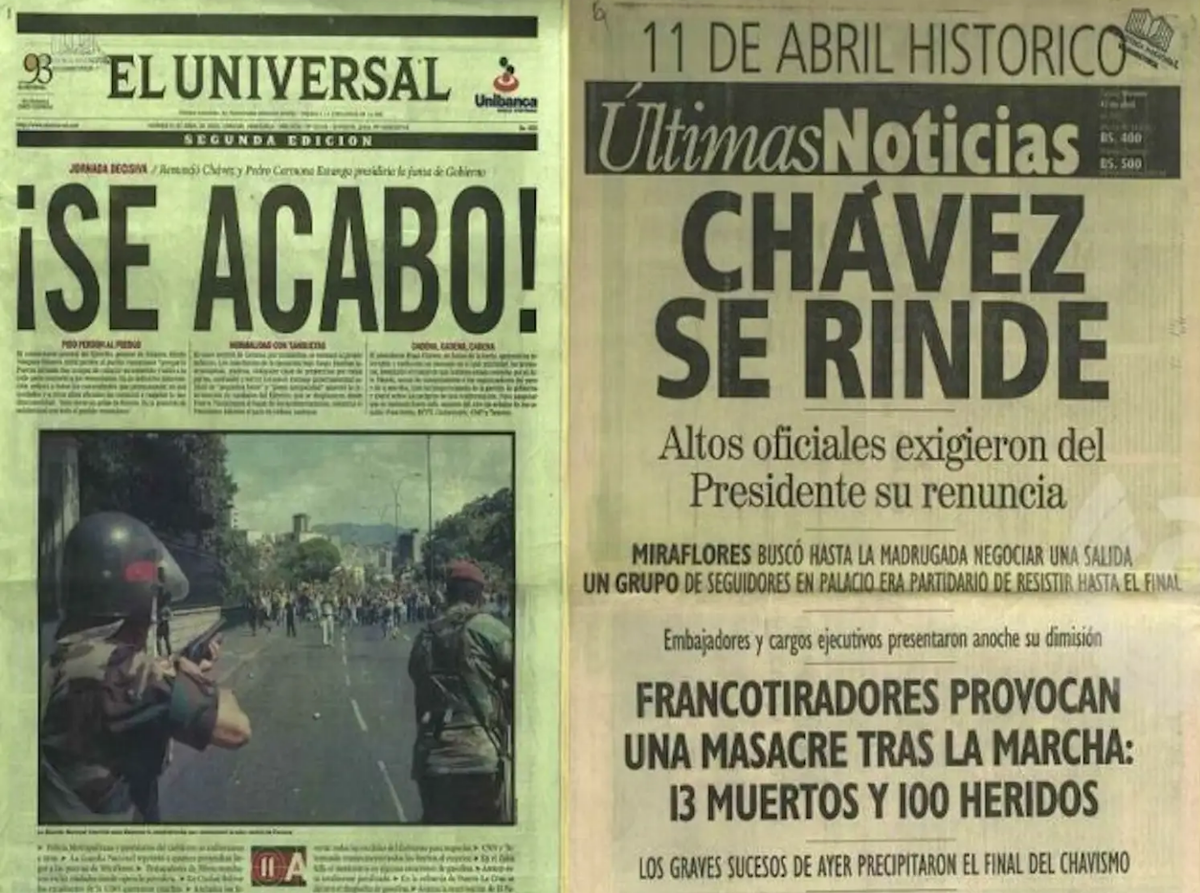

Hugo Chávez was sworn in as Venezuela’s President in February 1999, following an election marked by the second weakest postwar turnout the year before. Chávez replaced the democratic 1961 Constitution with a document which Freedom House considered to have de facto “abolished congress and the judiciary” , creating “a parallel government of military cronies.” Notably, he had done so unlawfully, because the laws at the time gave amendment power to Congress rather than a referendum — weakening the legal basis for Venezuela’s current government. For most of the next 14 years, Hugo Chávez remained in power using increasingly questionable elections. During the 2000 election, polling officials were replaced with loyalists who agreed to cut voting short. After the failed recall of 2004, peer-reviewed articles found that official results were likely manipulated, and reached similar conclusions upon Chávez's re-election in 20121.

After Chávez’s death in 2013, Nicolás Maduro took power in a similarly undemocratic manner: his reported margin in 2013 was less than half the votes cast by people with death certificates, and his self-declared re-elections in 2018 and in 2024 are not recognized by any democratic observers. Conversely, independent tallies from the last election gave centrist candidate Edmundo González a 2:1 lead, and their authenticity has been supported by academic statistical analysis. The clearly arbitrary nature of the regime’s hold of power now faces a rival who verifiably represents the population, and it lacks the support of the judiciary and legislature, which it forced into exile due to the opposition victory in the 2015 congressional elections.

On the domestic front, Socialist Party autocracy has presided over a catastrophic collapse in real output. Data for the past three years is nonexistent, but estimates by the Madison Project Database point to GDP being halved since 1999. Models for inflation also vary but suggest a peak in the tens of millions of percentage points. Rather than a decline in oil prices in 2014, economists signal that the crisis was caused by mismanagement of its nationalized industries, the seizure of private property, and price controls. Evidence of crimes against humanity in the country has also grown. Under Chávez, one report found 8,700 state-sanctioned killings from 2002 to 2007, alongside 350 ‘disappearances’ denounced in 2004 alone. More recently, a UN-backed Venezuelan NGO, Provea, counts 45,000 cases of torture, Human Rights Watch recently reported about 20,000 extrajudicial murders, and Amnesty International accused the regime of ‘disappearing’ 2,400 protestors after the last election. Venezuela is therefore experiencing an economic crisis similar in magnitude to others, such as the recent Lebanese liquidity trap or a wave of defaults in Latin America in the early 1980s, where significant foreign assistance was needed to present a viable solution. Police abuses have also escalated into the kind of systematic violations that international law is concerned with, further showing the need for global involvement.

Amidst outrage over human rights violations and growing political anger over drug trafficking, Western leaders have begun to side with the region’s conservatives, who long attacked Chávez as a dictator. Donald Trump has been especially aggressive since his re-election in 2024: his administration conducted 16 strikes against boats accused of carrying drugs in the Caribbean, the Central Intelligence Agency was given authorization for covert operations within Venezuela, and a military buildup in the Caribbean bolstered the U.S. presence in the region to its highest levels since 1994.

Throughout late 2025, the White House offered conflicting signs about its intentions. On the one hand, invasion would have left no need to cooperate with the (presumably crippled) army; the opposition (likely President Edmundo González) would have a free hand. But U.S. forces in the area are insufficient for an invasion, so it is even now improbable. Alternatively, a negotiated exit has clearly been decided against, but pressure within the armed forces was the cause of most transitions to democracy during the Cold War in Latin America. Chavism does not have a strong hold on the military, either: it supported a failed counter coup in 2002 and some officers have defected since 2019. The January 3rd operation that resulted in the arrest of Nicolás Maduro falls somewhere in between these two extremes and, though promising, leaves many open questions.

The end of Maduro's reign will fundamentally change life for Venezuelans and leave a lasting impact on the international community. Two cartels targeted by federal law enforcement, Tren de Aragua and Cártel de los Soles, are fronts for the Socialist Party and have smuggled 250 tons of cocaine into the United States per year since 19992. Furthermore, Maduro had supported a holdout faction of leftist guerrillas in Colombia who contributed to a record 500 terror attacks in the first half of 20253, while Tren de Aragua is allied with Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, a Mexican criminal syndicate notorious for cannibalizing victims. The regime’s fall from power will also weaken Russia and Iranian anti-Israel proxies’ ability to grow within Latin America; the country has acted as a leading entry point for agents and material aid. Cuba’s totalitarian state, now the oldest autocracy in the hemisphere, could also fall if Venezuelan oil were cut off. Finally, it may alleviate the crisis generated by the mass exodus of refugees from the country; 65% of emigrants previously said they would return given regime change4.

No matter the circumstances of Maduro’s removal, support from the United States for the opposition's program will determine their success. Maria Corina Machado, the leader of the anti-Chávez movement, has made her distaste for socialism clear, but the country’s devastated institutions and weakened state capacity adds unique challenges to reform. To revive the crucial oil sector, the sale of the state’s monopoly to foreign investors is needed, but only possible if the U.S. lifts sanctions on the new government and considers a credit to finance these imports. Privatization removes the largest burden on the deficit and injects liquidity into the Central Bank, without which reducing inflation is unrealistic. However, the bolivar is irreparably hyperinflated, and Venezuela would need at least $44bn in reserves to credibly redenominate. Again, Washington could come to their aid by reviving the successful Brady Plan for debt restructuring in the 1990s. Scholars link liberalization with the decentralization of economic power, implying that success on this front is crucial for protecting a new democracy long-term5.

However, the continuation of military and political elites makes a full break from the former dictatorship difficult. For one, generals creating presidents can also unmake them: Argentina’s Arturo Ilia, voted into office in 1963 but installed by the army was himself later ousted. Six coups occurred in Argentina between 1930 and 1983, a cycle whose end is attributed to the decision to try junta leaders for war crimes. This is not impossible; the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda were both able to indict commanders without provoking a rebellion amongst enlisted soldiers. While the Attorneys General of several countries have determined crimes against humanity have and are occurring, a trial would expose public opinion to the worst atrocities like nothing else can. It would also weaken the army’s leadership to the point where they would be unable to prevent an end to conscription or the dispersal of paramilitary units, hopefully, as it did in Argentina, leaving the military too weak to interfere in politics.

Finally, while adjudicating, under international law, crimes against humanity committed in Venezuela would clearly be beneficial for the nation's citizens, it is also a necessary and valuable opportunity for the global community to reevaluate and reform a legal framework that has accumulated an embarrassing number of failures in recent years. Firstly, at an institutional level, the ICC’s inquiry has stalled, with the prosecutor recently made to recuse himself due to his own financial ties to Maduro. Moreover, rules are meaningless in the absence of enforcement, and 18 Latin American countries which are signatories of the Rome Statute have admitted Maduro as a visitor without fulfilling their police obligations. One reason why enforcement has been sporadic at best is that complicity charges, originally designed to hold “by-standers” accountable, are rarely bought. Cases such as Lula da Silva, who provided Maduro 20,000 gas canisters for crowd control before the election, could set a new precedent. A Yugoslavia-era found that it is unnecessary to prove that a defendant intended a crime to occur or that their aid was decisive in an offense, just that they knowingly facilitated the act. In short, it is very likely that the leaders of other countries would become far more judicious in complying with international law during foreign dealings if they were liable for it. While Maduro is responsible for what has been done in Venezuela, just as Assad is in Syria or Putin in Ukraine, these tragedies would not have occurred without external support, and international law must evolve to acknowledge that if it is to effectively dissuade similar acts of cruelty.

Notes

- Amnesty International. “Amnesty International Report 2009 - Venezuela.” Refworld, May 28, 2009. https://www.refworld.org/reference/annualreport/amnesty/2009/en/67700.

- Amnesty International. “Venezuela: UN Rights Council Should Renew Experts’ Mandate.” Amnesty International, September 12, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/09/venezuela-la-onu-debe-renovar-el-mandato-de-expertos-independientes/.

- The Associated Press. “Trump Administration Announces 16th Deadly Strike on an Alleged Drug Boat.” NPR, November 5, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/11/05/nx-s1-5599008/trump-administration-16th-strike-drug-boat.

- Barnes, Julian E, and Tyler Pager. “Trump Administration Authorizes Covert C.I.A. Action in Venezuela.” The New York Times, October 15, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/15/us/politics/trump-covert-cia-action-venezuela.html.

- Brian Fonseca and Fabiana Sofia Perera | November 4, 2025. “What Will Venezuela’s Military Do? History Offers Hints.” Americas Quarterly, November 4, 2025. https://americasquarterly.org/article/what-will-venezuelas-military-do-history-offers-hints/.

- Center for Preventive Action. “U.S. Confrontation with Venezuela | Global Conflict Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations, October 21, 2025. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/instability-venezuela.

- Corrales, Javier. “Democratic Backsliding through Electoral Irregularities: The Case of Venezuela.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, no. 109 (April 30, 2020): 41–65. https://doi.org/10.32992/erlacs.10598.

- Delgado, Antonio María. “U.S. Poised to Strike Military Targets in Venezuela in Escalation against Maduro Regime.” Miami Herald, October 31, 2025. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/venezuela/article312722642.html.

- “Fear for Safety/Use of Excessive Force.” Amnesty International, March 4, 2004. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/es/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amr530032004en.pdf.

- Flaherty, Anne. “What Would Strikes on Venezuela Look like? US Target List Expected to Include Ports, Airports Used by Drug Smugglers.” ABC News, October 31, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-made-decision-strike-inside-venezuela/story?id=127059661.

- Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 1999 - Venezuela.” Refworld, January 1, 1999. https://www.refworld.org/reference/annualreport/freehou/1999/en/94810.

- Guiffard, Jonathan. “Trump vs. Venezuela: Scenarios for an Impending War.” Institut Montaigne, April 11, 2025. https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/trump-vs-venezuela-scenarios-impending-war.

- Human Rights Watch. “World Report 2023: Rights Trends in Venezuela.” Human Rights Watch, January 20, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/venezuela.

- Jiménez, Raúl, and Manuel Hidalgo. “Forensic Analysis of Venezuelan Elections during the Chávez Presidency.” PLoS ONE 9, no. 6 (June 27, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100884.

- Levinson, Reade, Ricardo Arduengo, Idrees Ali, Phil Stewart, Mariano Zafra, Jon McClure, Vijdan Mohammad Kawoosa, Clare Farley, Michael Pell, and Jonathan Saul. “How the US Is Preparing a Caribbean Staging Ground near Venezuela.” Reuters, November 2, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/graphics/USA-CARIBBEAN/MILITARY-BUILDUP/egpbbnzyrpq/.

- Lizarazo, Laura. “Colombia’s Terrorist Violence Aftermath.” Americas Quarterly, August 28, 2025. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/colombias-terrorist-violence-aftermath/.

- Magid, Shelby, and Imran Bayoumi. “Facing the Threat of US Strikes, Maduro Has Requested Russia’s Help. He Shouldn’t Expect Much.” Atlantic Council, November 4, 2025. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/facing-the-threat-of-us-strikes-maduro-has-requested-russias-help-he-shouldnt-expect-much/.

- Martialay, Ángela, and Esteban Urreiztieta. “La Audiencia Nacional Ordena a La Policía Investigar Los Pagos de Venezuela a Los Fundadores de Podemos.” El Mundo, November 17, 2021. https://www.elmundo.es/espana/2021/11/17/619548a9e4d4d8a6498b45cf.html.

- Matheus, Juan Miguel. “How Venezuela Became a Gangster State.” Journal of Democracy, 2025. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exclusive/how-venezuela-became-a-gangster-state/.

- Mebane, Walter R. Rep. Eforensics Analysis of the Venezuela 2024 Presidential Election. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Institute for Political Research, 2024.

- Murphy, Robert. Rep. National Drug Threat Assessment. Washington, D.C.: Drug Enforcement Administration, 2025.

- Prazeres, Leandro. “Maduro: Brasil Exportou Spray de Pimenta à Venezuela Às Vésperas de Eleição Contestada.” BBC News Brasil, January 9, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/articles/cvgpn305g1ko.

- Prosecutor v. Furundžija (Trial Chamber II December 10, 1998).

- Ruiz, Roque, Shelby Holliday, and Carl Churchill. “See Advanced Weaponry the U.S. Is Deploying to the Caribbean.” The Wall Street Journal, October 14, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/us-weapons-caribbean-graphics-44d9e5e5.

- Situation in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela I (ICC September 2, 2025).

- Tiwari, Siddharth. Working paper. Assessing Reserve Adequacy - Specific Proposals. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2015. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2016/12/31/Assessing-Reserve-Adequacy-Specific-Proposals-PP4947.

- “Treasury Sanctions Venezuelan Cartel Headed by Maduro.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 25, 2025. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0207?utm.

- United States v. Nicolas Maduro Moros, 1:11-CR-205 U.S. Department of Justice (U.S. Department of Justice Archive 2020).

- Vinogradoff, Ludmila. “La Década Oscura de Nicolás Maduro.” Clarín, May 21, 2024. https://www.clarin.com/mundo/decada-oscura-nicolas-maduro-45000-casos-violaciones-derechos-humanos-10000-ejecutados-fuerzas-seguridad_0_qzHK9jUDDZ.html.

- Young, Benjamin R. “It’s Time to Designate Venezuela as a State Sponsor of Terrorism | Rand.” RAND, August 22, 2024. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/08/its-time-to-designate-venezuela-as-a-state-sponsor.html.